|

| CW Jefferys, Voyageurs and Raftsmen on the Ottawa about 1818 |

As my followers know I have been studying all aspects of Voyageurs lives for many years.

|

|

The Beef Shoe from Musée de la Gaspésie

|

|

|

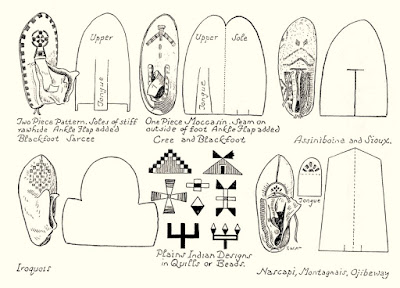

Indian Moccasins by CW Jefferys |

2025 addition courtesy of Grok xAI...

The Cordonnier's Craft in the Heart of New France

In the bustling cobblestone streets of Montréal in the early 18th century, where the sharp clang of blacksmith hammers mingled with the salty tang of the St. Lawrence River drifting through open workshop doors, Jacques Marié dit Lemarié (1687-1742)(our 6th great-grandfather), a maître cordonnier of renown, bent over his worn oak bench, his calloused fingers deftly stitching layers of thick cowhide under the flicker of a tallow candle. Born in Neuville amid the rugged frontiers of New France, Jacques had inherited a legacy of craftsmanship from a line of resilient French settlers—his father Charles Marier dit Ste-Marie and mother Marie Madeleine Garnier dit Laforge had instilled in him the art of turning raw hides into tools for survival. By 1721, married to Marie Angélique Duquet dit Desroches in Rivière-des-Prairies, he had fathered a growing family, their modest home echoing with the laughter of children like Marie-Angélique and Jacques Jr., while the scent of curing leather permeated every corner, a constant reminder of his trade's vital role in the fur empire.

As a master shoemaker, Jacques specialized in souliers de boeuf—those sturdy, unyielding moccasins that bridged the wild ingenuity of Indigenous designs with the robust practicality of colonial needs. Each pair began with the selection of prime cowhide, tanned to a deep mahogany sheen in vats bubbling with oak bark solutions that filled the air with a pungent, earthy aroma. He cut the soles thick and broad, double-layered for the punishing portages where voyageurs hauled canots over jagged rocks, their feet sinking into mud that squelched like wet clay. The uppers, soft yet resilient, were molded from supple leather, often reinforced with rawhide laces drawn tight like bowstrings, ensuring they hugged the foot through endless days of paddling foaming rapids or trudging snow-laden trails. Jacques would pound the hides with a wooden mallet, the rhythmic thuds echoing like distant thunder, before sewing them with waxed sinew threads that resisted the bite of river water and the grind of gravel.

Word of his craftsmanship spread among Montréal's merchants and outfitters, who commissioned dozens for their voyageur crews. Imagine a crisp autumn morning in 1730: a burly engagé like your distant kin Gabriel Pinsonneau—though generations apart—might have stepped into Jacques's shop, the bell tinkling softly as he entered, carrying the faint musk of beaver pelts from his last expedition. "Maître Lemarié," he'd say, his voice gravelly from chansons sung around campfires, "I need shoes that won't fail me on the Detroit run—something to outlast the devil's own portages." Jacques, wiping sweat from his brow with a leather apron stained by years of toil, would measure the man's feet with a notched stick, then set to work, hammering brass tacks for extra grip and rubbing in bear grease that left a glossy sheen, repelling the chill spray of the Ottawa River. These souliers de boeuf weren't mere footwear; they were lifelines, blending the soft, silent tread of deerhide moccasins worn by coureurs des bois—often beaded intricately by Indigenous women at posts like Michilimackinac—with the enduring strength of ox leather, perfect for the hivernants overwintering in frozen lodges.

Jacques's legacy wove through the veins of New France's fur trade, his shoes carrying men like the Lasselle brothers' hires across vast waters, their soles imprinting the paths that mapped a continent. By the time of his passing in 1742, buried in the soil of Pointe-aux-Trembles where his descendants would continue the craft, his work had outfitted countless souls chasing fortunes in pelts. In the glow of his forge, amid the scrape of awls and the warm scent of polished hides, Jacques Marié dit Lemarié embodied the quiet artisans who armed the adventurers, one stitch at a time, ensuring the river's call was met with feet unyielding.

Hello! Amazing article, I'm actually working on a big story for my site on beef shoes and other native and native-derived footwear and I was hoping that you might be available for a chat. You can reach me at ben [at] stitchdown.com Thank you!! -Ben

ReplyDelete